AshtaNayika Paintings: The Eight Heroines

- Omkar Shrikant Pradhan

- Mar 18, 2021

- 22 min read

Composition and Semiotic Analysis by Omkar Pradhan

“यथा सुमेरू: प्रवरो नगानां यथाण्डजानां गरुड: प्रधान:I

यथा नराणां प्रवर: क्षितीशस्तथा कलानामिह चित्रकल्प” II ४३:३९ II

Viśṇudharamottara Puraṇa

As Sumeru is the best of mountains, Garuda, the chief of birds, and a lord of the earth, the most exalted amongst men, so is painting the best of all arts.

(Tr. by Stella Kramrisch, 1928)

Introduction

The visual art in ancient India had its own space among all other art forms. The art of painting in ancient India had a certain importance. Atthasalini, a famous Buddhist text describes the essence of art i.e., painting as -

“कथं चित्तकरणताया ति ? लोकस्मिं हि चित्तकम्मतो उत्तरिं अञ्ञं चित्तं नाम नत्थि I”

“There is no art in the world more variegated than the art of painting.”

(Tr. by Maung Tin, 1921)

This example of a Gatha (verse) from Atthasalini suggests the importance of Chitra (painting) as a versatile, and an imaginative form. Similarly, Chitrasutra of Viśṇudharamottara Puraṇa also defines,

“….कलानामिह चित्रकल्प” and “कलानां प्रवरं चित्रं…”

“The finest among arts is painting.”

Since ancient times (1st/2nd century BC/AD – 5th/6th century AD) we have had great examples of fine art. The legendary murals from Ajanta caves exhibited the numerous imageries of art elements as well as the influence, concept, metaphor and the philosophical thoughts of their genre. To infer, the ancient Indian art of painting had its own peculiarities which later influenced other regional art of paintings in many aspects. However, the philosophy, concepts, metaphors and other representations found in this art, made this form more versatile, narrative, symbolic, decorative and even metaphysical. Many such diverse aspects of Indian paintings influenced the subsequent periods of paintings in vast regions of India.

In the mediaeval period, under the Mughals, Indian art of painting took a great sway in its manifestation. Royal patronage helped this new idiom of the art of painting become the zenith of new Indian art. It was a great amalgamation of Persian, local and regional art forms. These amalgamations gave birth to different royal as well as regional schools and styles in India known as Mughal, Rajasthani, Pahadi, Deccani etc. This was an innovative and a small expression of paintings, mostly done on paper, arose to be known as miniature paintings. Earlier conducts of kings or royalties, stories, epics stories, the scenes from royal courts, royal portraits were main subjects of these paintings. Whereas Hindu mythology, epics and Puraṇic stories and paintings on music, i.e., Ragmala paintings were introduced. These all became the subjects of painting in different principalities or the regions, under the kings and their subordinates.

It so appears that Indian artists have portrayed their compositions with various elements of nature; including flora and fauna, colours and symbols, even the celestial beings which they visualised by their own understanding of philosophy and age-old literature. While depicting complex figures they utilised their aptitude by surrounding various elements of nature. Aesthetically they added emotions i.e., bhava and rasato make them animate. Fascinatingly, the perception of figures by Indian artists as described by Jayamangala in his commentary on Kamasutra states,

“रूपभेदा: प्रमाणानि भावलावण्ययोजनम्I

सादृश्यं वर्णिकाभंग इति चित्रं षडंगकम् II”

“Differences in appearances, proportions, the blending of feelings with grace, resemblance with colour hues are the six limbs of paintings.”

However, among these, some elements are visible whereas some are inner or mental expressions. Similarly, Buddhist text like Attasalini also describes the creation of mental state of art, reflecting the renowned Jatakastories of Ajanta caves.

The compositions in each frame, in paintings or even in sculptural panels, are mostly full of action. Often, they are animated, decorative or even static. Vertical, multiple perspective or centralized figures are used to complete the depictions. Mostly these depictions are narrative in form. The entire space of portrayal is distributed into many segments, with multiple small spaces, surrounding the main subject. Colours also have symbolic meanings and are accordingly used to show a particular figure. Flora and fauna too have their own peculiar meanings. Signs and symbols and cantos/verses from celebrated texts are often employed to add feelings or sentiments in the art.

Finally, as mentioned in Viśnudharmottar Puraṇa of 5th/6th century AD. The art of painting is inter-connected to other performing and visual arts, such as sangit, nrutya abhinaya, poetry, sculptures, etc. All these perspectives of art, are important; and make Indian art a distinct form of visual art.

However, the compositional elements in the Indian paintings are treated differently as compared to the art of painting in the west. As mentioned earlier that the Indian idea of painting is mainly based on ‘six limbs’ of paintings. When differences occur in nature, the painter should adapt and paint accordingly but the proportions mentioned are based to form the divine rhythm of body, synchronising mainly with the nature. For instance, Rajivalochana Rama i.e., the eye of Rama resembles the petals of lotus, or Minakshi i.e., the shape of the eyes like a fish. Here, blending of feelings are most important, i.e., ‘rasa’ though it is the base of all art forms. Finally the use of colours or hues in the figures or any other entity in the picture is more important. As mentioned earlier it is more symbolic. Interestingly, the symbolic identity of colours convey the different moods, feelings and movements. In ancient literature, most of the colours are associated to the different activity, the psychology, notions and even rasa etc. Here, one can observe the image of Shiva, when shown in white as auspicious, calm or in the Yogic, meditative gesture, symbolising grace and creation (Utpatti), whereas, when shown in red, he is seen to be more aggressive towards the Asuras or symbolises continuance (Sthiti), when shown in black, he symbolises destruction (Laya). The above given example is not only restricted to Shiva, but other subjects as well, Interestingly in Yogic Sciences, the body is divided into a number of Chakras, which are associated with particular colours. Colours in the Indian Philosophy emancipate the divine or the universal energy.

With this brief introduction of colours, one can understand that in Indian painting, the perspective is different from that of the Western realistic paintings, which with the help of light and shadows (highlights, mid-tones, shadows) are painted in a more dimensional form; whereas, in Indian paintings the dimension (here contrast) is achieved with the help of colour gradation, zones etc. which in turn create a sense of multiple depths as mentioned earlier, to the paintings.

To understand miniature paintings, though it is an amalgamation of the Persian and the other regions as well, the subject of our concerned study is related to the Nayikas, the heroines from the ancient Indian literature hence, the idea and notions in Indian paintings are necessary to analyse the colour palettes, semiotics, etc. Hypothetically, it enables us to understand the pictorial frame of Indian paintings, with reference to the Indian miniatures.

Understanding the Concept and Classification of Nayakas and Nayikas

From the perspective of Poetry Rhetoric and Drama, as well as Śrungara-Erotics, Indian writers have been keen in classifying the Heroes and Heroines (Nayaka and Nayikas) in very well-defined types. We can study these classifications in some of the ancient Indian classics such as Bharatiya Natyashastra, Sahitya Darpaṇand Kamasutra. Many vernacular literature (poetry) works of Hindustan, such as Keshavdas’ Rasikapriya, Biharilal’s Satasaiya and Jaswant Singh’s Bhasha Bhushaṇ being its primary examples.

The oldest Classification can be traced in the Natyashastra wherein Bharata Muni defines fourteen Nayakaor the types of Hero-lovers in the following manner with respect to their Swabhava (Nature), as articulated in The Eight Nayikas by pioneering and celebrated historian, philosopher of Indian art Ananda K. Coomaraswamy as - lover, beloved, gentle, lordly, possessive, animated, pleasing, miscreant, evil, untruthful, refractory, braggart, shameless, brutal.

Whereas, in Sahitya Darpaṇ and Bhasha Bhushaṇ, Nayaka are classified majorly in four main categories - Anukula/faithful (to one beloved), dakshina/impartial (kind to one while loving another), satha/cunning (both unkind and false) and dhrshta/shameless (indifferent to blame).

In Rasikapriya’s classification of the above, anukula is replaced by the term atula (meaning the same), by keeping all the other attributes common. Further, in texts like Bhasha Bhushaṇa, Rasikamanjiri a more defined classification can be seen. This classification is based on the type of the hero-lover - husband (pati), paramour (upapati), one who resorts to hetairai (vaisika).

If we further study Bharatiya Natyashastra, heroes and heroines are classified into three more categories - worthy (uttama), unworthy (adhama), mediocre (madhyama).

The concept of Nayika/Heroine occupies a more detailed space in Literature of Dramaturgy and is more erotic than that of Nayaka/Hero. Coomaraswamy explicates this perception with a quote of Schmidt, that

“…is quite natural, since it is men that are classifying women; had the situation been reversed, the proportion might well have been different. Moreover, we can easily allow that a Woman is a much more interesting and many-sided object to study than Man,” Schmidt.

The very first basic classification of Heroines/Nayikas with respect to their relationship with the beloved appears in Kamasutra as - maiden, wife and hetaira.

Later on in Ratirahasya, women in general, based on their appearance are classified as- mrgi (gazelle-like), vadava (mare-like) and hastiṇi (elephant-like).

As per Ratirahasya, Anangaranga, Bhasha Bhushaṇa and Rasikapriya, a better known classification of women in the descending order of their merit - padmini (lotus), chitrini (variegated), shankhini (conch) and hastini (elephant-like).

Further, Ratirahasya classifies women as per age into - bala (up to 16 years), taruṇi (16 years to 30 years), praudha (30 years to 50 years) and vriddha (55 years and above).

Sahitya Darpaṇ, Bhasha Bhushaṇ further classifies women into the following type - swakiya (one’s own), parakiya (another’s) and samanya/sadharana (anybody’s).

Swakiya is further divided into - mugdha (artless/youthful), praudha (mature) and madhya (adolescent).

There are majorly three phases in the life of every Nayika, which could be classified into - navodha (newly married), udha (childish) and manini (attitude).

Ashta Nayika: The Eight Heroines

The concept of Ashta-Nayika can be traced back to the 2nd Century BC and 2nd Century AD, where the term ‘Ashta Naayika’ appears for the first time, in Natyashastra, a key Sanskrit treatise on Indian Performing Arts, authored by Bharata Muni.

“तत्र वासकसज्जा वा विरहोत्कण्ठितापि वा I

स्वाधीनपतिका वापि कलहान्तरितापि वा II१९७II

खण्डिता विप्रलब्धा वा तथा प्रोषितभर्तुका I

तथाभिसारिका चैव इत्यष्टौ नायिका: स्मृता: II१९८II”

(Classification with nomenclature, translated and elaborated below)

Ashta Naayika (Nayika-bheda) is a collective name for the eight types of Nayikas or the Heroines. These eight Nayikas represent eight different types of states or Avasthas in relation to her hero or Nayaka.

It has been used in the Indian paintings, literature, sculptures as well as in Indian classical dance, as the most common states of the romantic heroine.

The classification is further detailed in various other treatise as - Sahitadarpaṇa (14th Century) and Dasarupaka (10th Century)

And in poetics & erotic’s like: Kamashastra, Kuttanimata (8th – 9th Century) based on courtesans; Panchasayaka, Anangaranga and Smaradipika.

In Keshavdasa’s work Rasikapriya (16th Century), a Hindi poetic; a detailed work on the concept of Ashta Naayika can be witnessed. In most of the situations, Radha can be seen in the roles of these various Nayikas, whereas Kṛiśhna can be seen as her Nayaka.

The love between Radha & Kṛiśhna is represented through the domination of lyrics, from the consciousness of Radha in the Hindustani classical music; the semi-classical genre thumri, imbibes the moods of Radha, as the concept of Ashta Nayika revolves around the passionate love of Radha towards Kriśhna.

It is also believed that there are three ways in which the Lover may first see the Beloved - through a dream, through a picture and face to face.

Nomenclature and Identification of AshtaNayikas

It can be observed that, the lover and the beloved are represented as Radha and Kṛiśhna respectively in the Indian paintings.

Ashta Nayika has been one of the keen subject of the Indian Pahari paintings.

परिस्थिती-अनुसार नायिका-भेद

ये सब जितनी नाइका, बरनी मति-अनुसार I

केसवदास, बखानियै, ते सब आठ प्रकार I१I

स्वाधीनपतिका, उत्कहीं, बासकसज्जा नाम I

अभिसंधिता बाखानियै, और खंडिता बाम I२I

केसव प्रोषितप्रेयसी, लब्धबिप्र सु आनि I

अष्टनायिका ये सकल, अभिसारिका सु जानि I३I

Acharya Keshavdas kruta Rasikapriya (1962.23)

The above lines from Rasikapriya, by Acharya Kesavdasa, a 17th century Sanskrit pandit and Hindi poet, who composed a famous collection of poems. He describes the eight Nayikas according to the Natyashastraof Bharat Muni and his understanding. He mentions in his work, that there are eight forms of Nayikas.To comprehend the basic idea of eight Heroines i.e. Nayikas, the short introduction with description and synonyms of the Nayikas, are extracted from “THE EIGHT NAYIKAS” excellently described by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy.

(a) Swadhinapatika, Swadhinapatika; she whose beloved is “in her bandoun”, is subject to her.

(b) Utkala, Utka, Utkaṇṭhita, Virahotkaṇṭhita; she who is alone and expectant or yearning.

(c) Vasakaśayya, Vasakasajja, Sajjika, Sajjita; she who waits by the bed.

(d) Abhisandhita, Kalahantarita, Kupita; she who is separated from her beloved by a quarrel, i.e. as a result of her own unkindness.

(e) Khanḍita; she who is offended.

(f) Proṣita-patika, Proṣita-bhartṛka, Proṣita-preyasi; she whose beloved has gone abroad.

(g) Labdhavipra, Vipralabdha; she who has made an appointment and is disappointed.

(h) Abhisarika; she who goes out to meet her beloved.

The introductory sections and individual characters or swabhavas of each Nayika, gives her physical or emotional acuities. Accordingly, in abhinaya or natya, and especially in the art of painting, artists seems to be well proficient in each described swabhava of Nayika. Interestingly, these paintings show a number of features through colours, signs and symbols, flora and fauna too. All these renderings reflect bhava as well swabhava.

In the following discussion we will try to understand each and every Nayika, with respect to her key identification points, and later on we shall try to analyse a few paintings with the help of the Semiotics prevailing in them.

(a)

Swadhinapatika Nayika

(she whose beloved is “in her Bandon”, is subject to her)

In the mansion of Radha, Krishna paints his consort's feet with auspicious red lac, popularly called mahawar, a dye extracted from beetles. Radha's attendant is amazed to witness this divine love. Kangra, 19th century. From the collection of The National Museum, New Delhi

Swadhinapatika Nayika is classified as standing/seated beside her lover, whereas he is seen gently massaging her feet, washing it, caressing her or applying lac dye on her feet. This is an evidence of her Lover’s complete subjection.

Swadhinapatikā Nāyika’s charm and gentleness is such that it leaves her lover, not only faithful but also her faithful salve.

Swadhinapatikā Nāyika is considered as the happiest Nāyika amongst the others.

Swadhinapatika Nayika Lakshana

Krishna spreads lotus petals using which Radha follows him at night by a lotus tank. 17th C. Malwa India.

From the collection of The National Museum, New Delhi, India

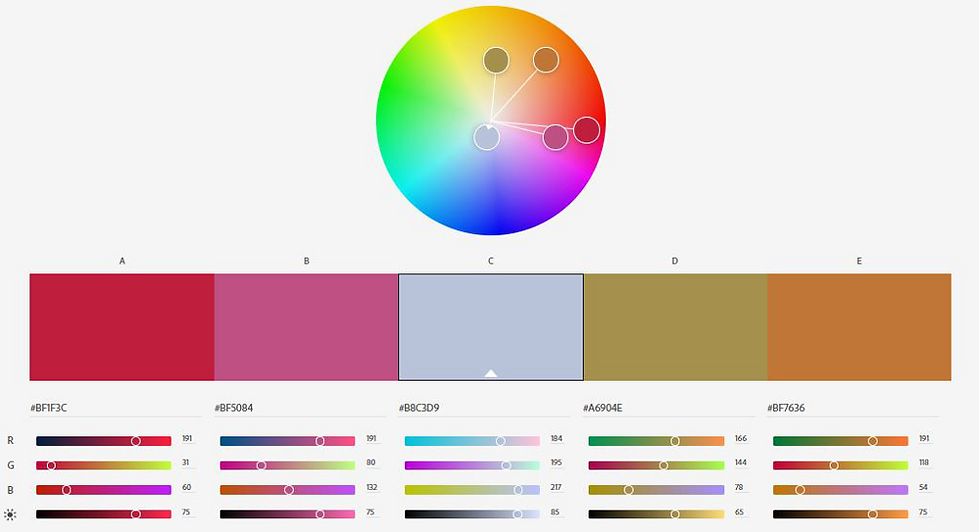

Color Palette

Palette (i)

Swadhinapatika Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis:

The use of complimentary colour scheme can be seen here, wherein the contrast is created with the help of yellow and orange on the foreground of the colour blue and its shades. The use of white to balance the mass of blue is evident and helps create a deeper contrast. A careful calculation of the warm colours is used to create harmony with the vast mass of the cool colours, which in turn gives rise to the mood of the theme. In terms of colour psychology, the colour blue is used here to portray night as well as it symbolises peacefulness, tranquility, stability, as well as the infinite Sky.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis:

The Nayika in the above miniature painting can be classified and identified as ‘Swadhinapatika Nayika’ as we can see Kṛiśhna spreading lotus petals for his beloved Radha, who can be seen walking over them. This painting is drawn in the oriental perspective, especially in Indian context here. The tree in the centre divides the scene into two symmetrical parts, which is the symbolic representation of the two mindsets and the equal-ness/one-ness of Radha-Kṛiśhna.

The branches of the trees, peacock feathers, eye-line of the monkeys etc. are smartly utilised by the artist to lead the viewer’s attention back to the subject. Such kind of leading lines can be seen in a lot of Indian paintings. In Indian paintings, Kṛiśhna is always painted using the colour blue and black, which denotes that Kṛiśhna is an avatar of Vishnu and that in turn signifies the “sky and infinity”. To maintain the privacy of the scene/moment, the artist has used the “frame within a frame” technique.

The presence of Banana trees, with inflorescence at the base of the painting, especially the occurrence of Banana flower signifies fertility/motherhood. All the trees present in the painting are blooming with flowers; the peeping monkeys becoming the witness in the scene adds to the creation of the romantic ambience as well as gives the viewer an indication of the mindset of the Nayika.

The body language of peacocks as well as the lyrical lines of the tree branches, gives us an illusion of the happiness of the scene. Peacocks, in Indian semiotics are considered as auspicious, as they are related to monsoons. 60% of the frame is filled with cool colours; mostly shades of blue to ensure the area visible is as infinite as the sky.

(b)

Utkanthita Nayika

(she who is alone and expectant/yearning)

The Anxious or Expectant Heroine (Utka Nayika), Folio from a Rasikapriya (The Connoisseur's Delights) of Kesavadasa. Rajasthan, Uniara, circa, 1760 or later.

Utkanthita Nayika is classified as the one who awaits her beloved impatiently at the place of their meeting. Generally this Nayika is seen standing beside or seated on a leaf-bed under a tree/beside a stream/at the edge of some groove, mostly at night. The presence of timid Deers, grazing, snuffing the winds and ready to dash away at the least sound, with the stillness of the water and the loneliness of the place is evident around her.

Utkanthita Nayika and Abhisarika Nayika are considered as the most poetic and the most appeared ones from the entire Ashta Nayika series in Indian paintings.

Utkanthita Nayika Lakshana

Plate (ii)

Utkanthita Nayika: Radha waiting for Kriśhna (From Google)

Color Palette

Palette (ii)

Utkanthita Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis

Bright orange is used as an element of contrast as well as to show the curiosity of the scene. The gradation of purple is used to depict devotion, mystery. The mass of white creates the element of innocence and alsostrikes a balance in the composition, whereas the gradation of bluish grey in the leaves around the Nayika depicts subdued, quiet and reserved emotions. Elements of green is used to symbolise calmness and create depth to the surrounding.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

The Nayika in the above given image can be classified as Utkanthita Nayika as we see her waiting for her Nayaka. The central composition is quite evident in this painting too and the Indian perspective can be observed. The asymmetrical imbalance, helps the theme of the painting to connect more towards desolation.

In the Indian school of composition, circularity plays a vital role. The circular leaf bed suggests that the wait is infinite. The branches of the tree are used as leading lines to divert the viewer’s attention back to the Nayikafrom any part of the frame.

The imbalance between the volumes of leaves and the flowers suggest the imbalance and the conflict between her thoughts. The presence of the doe, drinking water, is a symbolic representation of thirst, serenity and grace. The incomplete composition of the doe, signifies the incompleteness present in the theme.

There are three types of lotuses:

(i) Pundarika (White; blooms at night)

(ii) Kaumudi (Blue; blooms at night)

(iii) Padma (Pink; blooms in the morning)

The purposeful use of Pundarika lotus suggests the time of night as the light of the surrounding falls onto the stream and is being bounced back by the lotuses thus, illuminating the Nayika even at this dark hour of the night.

The gradation of the sky towards blue signifies that the wait for the Nayika is endless whereas the evident white patch around the Nayika suggests purity.

(c)

Vasakasajja Nayika

(she who waits by the bed)

The expectant lady, with peacocks representing the absent lover.

Mandi, ca. 1840 (From Internet)

Vasakasajja Nayika can be classified as the one, looking out of the door of her house, standing beside the bed and waiting for her beloved, while the maids can be seen preparing the house and the bed for the reception of Kṛiśhna .

Vasakasajjā Nāyika is a delightful Nāyika, which can be seen properly dressed for the union with her lover.

Vasakasajja Nayika Lakshana

Plate (iii)

Vasakasajja Nayika: Radha preparing for Krishna ’s arrival (From Internet)

Color Palette

Palette (iii)

Vasakasajja Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis

A very well executed symbiosis of complimentary colour scheme can be witnessed in this painting, wherein the painting is divided into two zones, the palette of Krishna is depicted in blue (cool) and the Nayika and her sakhis are shown in a warmer tone. White is used to create a balance between the cool and the warm tones. The subtle presence of red is used to depict love and create a contrast to the overall ambience. Green colour is used to represent tranquility, good luck, health.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

The Nayika in the above painting can be classified as Vasakasajja Nayika, as she is dressed to meet her beloved. The Indian composition as well as an asymmetric imbalance is evident in this painting. The first thing noticeable in this painting is the mass of blue, which indicates the presence of Kṛiśhna.

Interestingly, Kṛiśhna’s presence can be seen in two ways, one seen in the bushes observing Radha, and the other, seen in the reflection. The crowded compositional elements used in the surrounding of Radha determine her thoughts. The presence of immense banana flowers indicates fertility. Peacocks can be seen which indicate a new beginning, as well as rain and beauty.

The eye-lines and the gesture line of each character in this painting plays an important role in focusing the viewer’s attention to the central characters. The gushing of stream, jumping fishes depict the excitement of the moment.

Radha’s skin tone has more saturation of yellow, displaying the glow of her presence. The existence of the Padma Lotus (pink) hints at the time of the event.

(d)

Abhisandhita Nayika

(she who is separated from her beloved by a quarrel, i.e., as a result of her own unkindness)

From the collections of Govt. Museum and Art Gallery,

Chandigarh Miniature Painting Abhisandhita Nayika Kangra c. 19th century

Abhisandhita Nayika can be classified as the one parting from her beloved because of a quarrel.

This Nayika is mostly seen departing in deepest dejection from her beloved, whereas her lover is generally seen departing in anger.

Abhisandhita Nayika Lakshana

Plate (iv)

Abhisandhita Nayika: The separation (From Internet)

Color Palette

Palette (iv)

Abhisandhita Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis

The mass full of white is broken with the help of bright yellow and bright pink. In colour psychology, pink is a sign of hope. It is a positive colour, inspiring warm and comforting feelings, a sense that everything will be okay, whereas, yellow creates feelings of frustration and playful anger. The faded elements of green over the mass of pink are used to depict envy and dejection. Contrast is created with the help of these two colours only, the use of other colours are negligible.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

The evident separation portrayed in this painting can be a key factor in classifying this heroine as Abhisandhita Nayika. The symmetrical yet imbalanced composition with a lot of negative space hints at the separation of the two characters. The background behind the Nayika shows the emptiness, and a frame within a frame is used to divide these thoughts.

The lack of blue and the presence of a neutral ambience can be perceived, stating the physical absence of Krishna. The mass of pink, indicates the amalgamation of anger and love. The two pillows, drifted away from each other can be observed and adds more to the mood. Warm colours dominate the characters, whereas the atmosphere is evenly neutral further highlighting the emptiness.

(e)

Khandita Nayika

(she who is offended)

An illustration from a Rasikapriya series: Khandita Nayika, a heroine reproaching her lover. India, Pahari, Kangra , ca. 1810–1820

Khandita Nayika can be classified as a Nayika, who is offended by her lover in a playful manner.

She can be observed, questioning her beloved, in anger after they meet. She can also be considered as “possessive and insecure” towards her lover.

Khandita Nayika Lakshana

Plate (v)

Khandita Nayika, an illustration to Keshav Das's Rasikpriya, 1780 AD

(From Internet)

Color Palette

Palette (v)

Khandita Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis:

The major portion of the frame is filled with white which depicts innocence, calmness is contrasted with blue, symbolising Krishna and infinity, complimenting with yellow which symbolises happiness, cheerfulness and fun. The bright orange on the Nayika is used to show her curiosity, and the gradation of red elements depicts romance, and is balanced with a mass of Green.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis:

The body language of the characters suggests the questioning nature of the Nayika, and hence she can be classified as Khandita Nayika.

The painting has a balanced symmetry. Leading lines play a dynamic character in focusing the viewer’s attention towards the central character. Time of the event is suggested through the rising sun.

The corridor, through which Kṛiśhna has arrived, is depicted in Blue. The covered door behind Radha, shows her denial, whereas the open door through which we see the bed, suggests Kṛiśhna’s consent. The colour red helps in balancing the white mass.

(f)

Prositapatika Nayika

(she whose beloved has gone abroad)

Prositapatika Nayika, a disconsolate lady reclining on a bed, attended by an elder lady and two maids. Nurpur, ca. 1770-1780

Prositapatika Nayika can be classified as the one, sitting with her Sakhi, who is trying to comfort her as the time of Kṛiśhna’s return has lapsed and he has still not returned.

Prositapatika Nayika Lakshana

Plate (vi)

Prositapatika Nayika, Sakhi reassuring Radha (From Internet)

Color Palette

Palette (vi)

Prositapatika Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis

The mass of white, with a greyish blue sky is evident here to show the absence of Krishna. The only element of hope is depicted by pink through the curtain colour and the green scarf of sakhi. The red element of the carpet which fills the entire frame can be the psychological depiction of the relationship of the Nayika with Krishna.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

As seen in the above painting, the Nayika can be classified as Prositapatika Nayika as we see her Sakhitrying to comfort her.

The painting is symmetrically balanced. The neutral colour tone, with an evident mass of red, shows the anger in the mind of the Nayika. The arch of the mansion acts as a leading line and directs the viewer’s attention to the Sakhi and Nayika, later through the gesture lines and the eye line of Sakhi, we again see the Nayika. Frame within a frame is used to show the hollowness outside the mansion.

Void is shown through the grey skies and the empty white walls. The colour of the bed sheet is blue, which indicates her thoughts about Kriśhna.

(g)

Vipralabdha Nayika

(she who has made an appointment and is disappointed)

Vipralabdha nayika painting,

Jaipur, 1800, British Museum, London

Vipralabdha Nayika is classified as the one similar to Utkanthita Nayika, but in her case, the given time has passed yet her beloved hasn’t come to meet her. He has abandoned her. She can be observed tearing down her jewels and flinging them in the floor in despair.

Vipralabdha Nayika is further divided into:

· Purvanugraha

· Mana

· Pravasa

· Karunya

Vipralabdha Nayika Lakshana

Plate (vii)

Vipralabdha Nayika, a Forlorn Heroine

Punjab Hills, Himachal Pradesh, Kangra, ca. 1830

Color Palette

Palette (vii)

Vipralabdha Nayika Lakshaṇa Painting

Palette Analysis

Monochromatic colour scheme can be observed in this painting using the colour green and its shades, depicting envy and tranquility also symbolising balance and harmony. The white elements are used to create a contrast between the elements. Gold colour is associated with abundance and prosperity, as well as spirituality. The complete absence of blue can be seen in this painting.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

The abandoned state of this Nayika can be used to classify her as Vipralabdha Nayika. The painting is centrally composed. The mass of white and green are evident, and has helped in creating the contrast.

The reflection of the moon in the ‘still’ water can be seen as her mindset. Her attachment to that space, can be seen when she is tearing down her jewels and placing it inside the leaf bed, signifying memories. All the elements in the frame, the lines of the branches, the mass of the water, her hand gesture, grab the viewer’s attention to the Nayika itself.

The grey skies and the emptiness of the frame highlights the state of her mind.

(h)

Abhisarika Nayika

(she who goes out to meet her beloved)

Krishna abhisarika nayika, the nayika who goes out to meet her lover in the dark

phase of the moon. Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh, India.

Date: ca 1800-1825 CE

Abhisarika Nayika can be classified as a Nayika, who is on a journey to meet her beloved. She can be seen going through a lot of hurdles like snakes, ghosts etc. watching her. Her main objective being - meeting her lover.

Abhisarika Nayika is further classified in five types, depending on the time of her journey.

· Sukla Abhisarika Nayika (Full Moon)

· Kṛiśhna Abhisarika Nayika (Dark Night/No-moon)

· Diva Abhisarika Nayika (Day)

· Sandhya Abhisarika Nayika (Twilight)

· Nisha Abhisarika Nayika (Night)

Abhisarika Nayika Lakshana

Plate (viii)

Abhisarika Nayika, A painting from a dispersed Nayika series ca. 1810–1820

(From Internet)

Color Palette

Palette (vii)

Abhisarika Nayika Lakshana Painting

Palette Analysis

Dark grey is used to create the element of fear, mysteriousness, suppression. Lightening is used as the key light source to illuminate the scene. The use of yellow and orange on the Nayika symbolises excitement, enthusiasm, and warmth. The absence of blue is evident in the painting which denotes the absence of Krishna. The colour brown is used to create a sense of heaviness, sadness, and isolation. The colour green is also associated with materialism, envy, and it adds more to the feeling of loneliness in this scenario.

Semiotic/Compositional Analysis

As seen in the painting, this Nayika can be classified as Abhisarika Nayika (Kṛiśhna Abhisarika Nayika) as she is seen to be on a journey to meet her beloved.

This painting shows that precise moment, when the lightening has struck and the entire ambience along with the Nayika is illuminated. The lightening is used as the main source of illumination for the scene in order to create a scary environment.

Leading lines are used as a connecting tool between the Ghoul and the Nayika, whereas the saturation and the contrast divides them and brings our focus back to the Nayika. The owls present on the tree symbolise night. The tree branches bending towards the Nayika seem to be brittle which adds to the horror of the scene. The body language of the Nayika justifies confidence, fearlessness.

Snake is symbolised as death, however the bush in between the Nayika and the ghoul symbolises a new beginning. The dropping of the jewels by the Nayika supports her hurry to meet her beloved.

Samyog (Union)

Samyog is a state of union, in which the Nayaka and the Nayika becomes ONE. It is a form of completion. The below shown painting is based on the concept of Prakruti and Purush, wherein Radha is dressed in Kṛiśhna’s attire and Kṛiśhna is wearing Radha’s attire. The concept of Radha and Kṛiśhna is above all the barriers of gender; it is a pure form of love and dedication. Kṛiśhna symbolises infinity, so when we say that Radha and Kṛiśhna are becoming “one” it means that they are attaining an infinite state, which is beyond definition.

Plate (ix)

The Refection (From Internet)

Krishna with his Ashta Nayikas

Plate (x)

Apte, B.K. 1988. Maratha Wall Paintings, (Wai, Menavli, Satara, Pune)

Epilogue

What could possibly be the purpose of engaging with such an ancient theory? What relevance does it hold to the contemporary times?

The study of Ashta Nayika provides one with an immense knowledge about the universal emotions, and the way in which they can be depicted through the art of paintings, with numerous gestures and postures, signs and symbols, flora and fauna. The Indian method of depiction of emotion/s is rooted primarily in ambience creation. The spirituality, mythology present in the Indian method of storytelling seems to create a long lasting effect on the audience. An in-depth study of such an ancient theory may help in the rendering of different emotions, gestures, symbols, etc. in order to create mental emotions or Bhavas as a metaphoricalentity, to imitate personal impact on the viewers across diverse art forms.

The concept of Prakruti and Purush helps in the understanding of the infiniteness of nature. Miniature paintings employ the use of semiotics to create stories within a story, thus, highlighting the idea of circularity or infiniteness in the Indian philosophy as opposed to the Western philosophy. The study of miniature paintings provides one with a deeper understanding of composition, colours, hues, and moods too; and introduces an exposure to the unique practice of perceiving or “seeing” things in the Indian tradition. Paintings such as Ragamalas, etc. can be instrumental in understanding the rhythm of life through the art of music, and can help in its better visualisation. These paintings highlight the importance of metaphors, and their effective usage in order to convey a particular mood, thought and the beauty of many diverse aspects of mundane human life.

An engagement with the ancient texts reveal that all art forms are connected to each other, and in order to understand a particular form, one needs to have an understanding of the other. The idea of mise-en-scene in cinema can be looked upon through the lens of our traditional art forms, relaying an informed aesthetic sense for semiotic representations of the atmospheric elements across different genres of cinema. The concept of juxtaposing layered sonic images in cinema, that may or may not pertain to the idea of storytelling, can be redefined through the Indian perspective. If the concept of Nayakas and Nayikas is studied in depth by the performers across various art forms, their relation to that particular character or narrative would be stronger and deeper, as the human behaviour towards love and separation hasn’t really changed in general since ancient times, and hence may result in a far more successful performer-audiencerelationship.

Finally, there are several derivatives beyond my formed realisation that may yet highlight the importance of understanding the intricacies of ancient traditional text therefore, opening up a unique worldview that still remains largely inaccessible in the mainstream narrative.

An article by

Omkar Shrikant Pradhan

*This project was part of the study for the academic research carried out in the capacity of a student of Fine Arts, Cinema; and serves no commercial purpose whatsoever. Indian Society of Cinematographers (ISC) social media platforms or the Author himself do not claim any Copyright on the images shared in the article or intend to use it commercially. The Author has tried to mention the source of images to the best of his knowledge.

References

· Acharya Keshavdas Kruta Rasikapriya, 1962. Suchana aur Prasaran Mantralay Bharat Sarkar, Rashtriya Sangrahalay, Nayi Dilli.

· Coomaraswamy, A. K. 2000. The Eight Nayikas. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd. New Delhi.

· Art Passages.com

· The Modern Vernacular Literature of Hindustan by George Abraham Grierson

· Pandit Sivadatta and Kasinath Pandurang Parab, (edited). 1894. The Natyashastra of Bharata Muni, (Sanskrit Text), Kavyamala 42, Nirnay Sagar Press, Bombay.

· Maung Tin, 1921. ‘The Expositor (Atthasalinī)’ (edited) (Vol. 1), Buddhaghosa’s commentary on the Dhammasangani the first book of the Abhidhamma Pitaka, The Pali Text Society by the Oxford University press, Amen corner E.C.

· Stella Kramrisch, 1928. ‘The Viśṇudharamottara’ (Part III), A Treaties on Indian paintings and Image-making, Calcutta University Press, Calcutta.

· Randhawa, M.S. 1962. ‘Kangra Paintings on Love’, The Director Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Patiala House, New Delhi.

· Shiveshwarkar Lila, 1967. ‘Chaurapan̄chaśika’, A Sanskrit Love Lyric. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Patiala House, New Delhi.

· Wikipedia

· Apte, B.K. 1988. Maratha Wall Paintings, (Wai, Menavli, Satara, Pune). Secretory Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture, Mantralay Bombay.

· Dr. Shrikant Pradhan (Personal communication)

· Color Palette’s, Color Gradation and Color Wheels extracted from Adobe Color.

Comments